The British Newspaper Archive recently added the Woman’s Dreadnought to their roster. Edited by Sylvia Pankhurst throughout its run from 1914-24 and later titled the Workers Dreadnought, this East London weekly was a unique addition to the suffrage media landscape. Topics ranged from Marxist analyses of Irish Republicanism to Esperanto vocabulary lessons. Between the pages of the Dreadnought we can also find the fragmentary life stories of hitherto obscure activists. Excitingly, the digitization of journals such as the Dreadnought provides an unprecedented opportunity to shine a historical spotlight on these unsung fighters for suffrage and socialism.

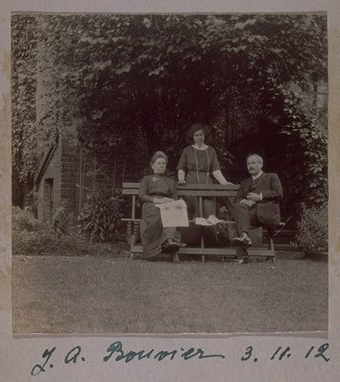

Madame Eugeníe Bouvier is one such relatively forgotten activist who has appeared on the sidelines of my research into suffragettes who became communists. Eugeníe Anna Bouvier was born Evgeniia Georgievna Weber in St. Petersburg in 1865, and married the Italian-born Emile Paul Bouvier, later a professor of French at King’s College London, in 1888. The precise date of their emigration from St. Petersburg to the United Kingdom is unknown, but we do know that the Bouviers chose South-East London’s Lewisham as a home and had a daughter there; Irene, born in 1893. In the following years Eugeníe, known also as “Madame Bouvier”, “J. A. Bouvier” or simply “Jeannie”, rose to prominence within the world of suffrage activism. In the foundational 1931 history The Suffrage Movement, Sylvia Pankhurst described her as “that brave persistent Russian.”

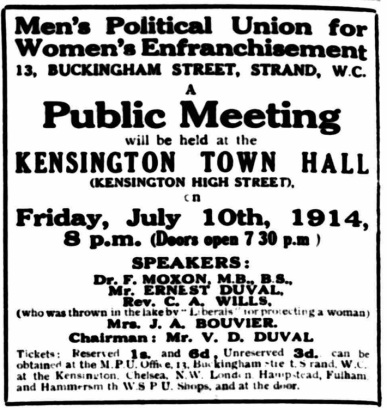

Eugeníe’s involvement in suffrage militancy has been diligently traced in posts on the blogs Running Past and Uncover Your Ancestors. While secretary of the Lewishman branch of the WSPU, she was one of the first militants to adopt the tactic of window-breaking in the summer of 1909, when nineteen WSPU members threw stones at Westminster to show, in Eugeníe’s words, “what we thought of the Prime Minister in refusing these ladies admission to the House of Commons.” Meeting notices in the suffrage press frequently record “Mrs. Bouvier” or “Mrs. J. A. Bouvier” as a speaker capable of attracting appreciative crowds. During the Great War, she became involved in Sylvia Pankhurst’s East London Federation of Suffragettes, which was itself expelled from its parent organization the WSPU in 1913, Until now, little was known of Eugeníe’s political afterlife.

The recent digitization of the Dreadnought has revealed some interesting twists in Eugeníe’s story. My first encounter with her was in a 1973 oral history interview conducted with Nellie Cohen, Sylvia Pankhurst’s personal secretary during the war. “Mrs Bouvier! I’ll never forget her” Cohen told her interviewer Lucia Jones “she was an astonishing creature. She was Russian – she used to do the translation.” The East London Federation of Suffragettes was an organization that underwent its own political journey, from a philanthropically-minded organization managing local maternity facilities into a revolutionary hub influenced and transformed by Lenin’s October Revolution. Tracing mentions of “Mrs. Bouvier” through the digitised Dreadnought, we can see that Eugeníe Bouvier remained on the committee of Pankhurst’s East London group as it transformed first into the Workers’ Suffrage Federation, then into the Workers’ Socialist Federation and finally became the Communist Party of Britain (British Section of the Third International) – confusingly, a different group to the Communist Party of Great Britain.

Given the political trajectory of the East London suffragettes, having the native Russian speaker Eugeníe as a member was undoubtedly useful to Pankhurst who was in personal contact with leading Bolsheviks. Conrad Noel, a Christian socialist who volunteered at the Fleet Street headquarters of the Dreadnought, remembered Eugeníe as an unusual figure who had lost all of her property in Russia’s revolutionary tide. When asked how she felt about the communist seizure of her family wealth, she reportedly replied: “They ought to have taken it from me years ago, and from all of us who lived on the backs of the people.” Clearly sympathetic with Bolshevik aims, Eugeníe gave speeches to East London audiences on the revolution in her home country and was reportedly a hit amongst the sizeable community of former subjects of the Russian Empire resident in East London.

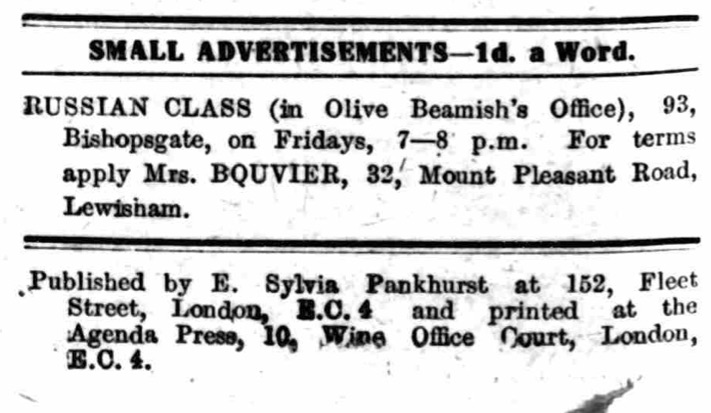

In total, more than 100,000 Russian Jews arrived in the East End of London between 1881 and 1914, fleeing anti-Semitic persecution in the Pale of Settlement. But as the curtains closed on the Russian Empire, the emergence of a new regime heralded the possibility of an era of tolerance, inspiring many to return to Russia. Sharman Kadish, in her brilliant work Bolsheviks and British Jews, writes that the exodus of Russian Jews returning home decimated the radical Jewish groups of the East End. Alongside this homeward movement of the diaspora, the early world of British communism began to see Moscow as a pilgrimage site for the faithful. Eugeníe capitalized on this newfound Russophilia infecting the British Left by offering weekly Russian language classes in the office of Cork-born suffragist Olive Beamish.

In 1920, the widowed Eugeníe decided to undertake a long-delayed return journey to Russia. Her daughter Irene was at this point a musician whose early career involved singing at suffrage gathering. It remains unknown whether or not she joined her mother on the one-way trip to their ancestral home. Eugeníe wrote to Sylvia Pankhurst in December 1920, enclosing a recipe for Russian kasha and noting that she hoped “to be off in Spring & have obtained passport from the Italian Consulate.” In the spring of 1921, the adverts publicising Eugeníe’s language classes in the Dreadnought ceased. Evidently, she was on her way to Moscow.

Eugeníe made her last appearance on the pages of the Dreadnought on 25 June 1921. A letter sent from Russia by the recently arrived ex-suffragette was printed with the title “MOSCOW AT LAST”. She described the journey across Europe in a diplomatic train, accompanied by comrades en route to the Third World Congress of the Communist International. Moscow was a city where many of the shops she once remembered were now closed and dilapidated but the people, on the whole, seemed “healthier, better dressed and cleaner”. Traversing Nevsky Prospect, Eugeníe found two people seated beside the monument to Catherine the Great holding copies of the English-language weekly The Communist. Eugeníe recognized the pair as Sidney Arnold, a Lithuanian writer and founding member of the Communist Party of Ireland, and an Irish woman whose name she could not recall (much to this researcher’s frustration!). In the summer of 1921, the curious and heady world of emigre communists resident in Moscow was just coming into existence. Eugeníe reminisced with relatives and secured work as an interpreter for the forthcoming Comintern World Congress. She signed off her letter: “Hard work and hard times are in front of us, but we must peg away and hope for the best.”

What became of Eugeníe after the Congress? Russian archival listings suggest she continued to work at the Comintern headquarters. The Comintern personnel files include a folder titled “Bouvier, Evgeniia Georgievna”. In fact, a disproportionate number of East London suffragettes found work in the Comintern’s imposing neo-classical building on Mokhavaya street. She was later joined by Rose Cohen, sister of Pankhurst’s secretary Nellie, Violet Lansbury, daughter of George and Minnie Lansbury, and May O’Callaghan, a polyglot and intellectual from Wexford, Ireland – all of whom had spent time working in Pankhurst’s East London offices on 400 Old Ford Road. Rose Cohen is the best known of these individuals, largely due to her tragic 1937 death as a victim of the Stalinist terror. Some of the East London Russians who returned after the Revolution, particularly those of an anarchist persuasion, met similarly dark ends in the Soviet state. However, there is nothing to suggest that Eugeníe’s death in Moscow in 1933 was anything other than natural.

With digital precision, we can now retrace the destinies of numerous suffragettes. Eugeníe Bouvier is an interesting example of both the post-1918 trajectory of former suffragettes and the histories of immigrant women who helped win the vote alongside their British sisters. When I travel to Moscow for my fieldwork in September, I look forward to seeing what hidden histories are resting in the personnel files of women like Eugeníe who migrated to the Soviet Union during the 1920s in search of adventure, employment, and a new political ideal.

Postscript – The Comintern File on Eugeníe Bouvier:

In September 2018, I spent a month in the Moscow archives working on my PhD project. I took some time to do more research into Bouvier and ordered her Comintern personnel file from the archive.

Alongside reconfirming biographical details that have been noted in the post above, the Comintern file sheds further light on Bouvier’s path to Moscow and her life there.

A precís of her political background submitted for membership vetting as a candidate of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union gave particularly intriguing biographical details: Bouvier noted that she had been forbidden from addressing meetings by the UK Home Office in 1917. Bouvier’s infraction, she suggested, was her activities demonstrating in London and the provinces “in support of B[olshevik] overthrow in Russia.” She wrote that in the spring of 1921 she worked with Maxim Litvinov, the Bolshevik emissary in London, translating documents into English. In May 1921, after discussions with Grigory Checherin, then People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs, Bouvier returned to Russia and took Soviet citizenship.

From then on, she worked in the English section of the translation department of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs (later taking up the same role in the Comintern). Bouvier appears to have taken on confidential work, also, as another document in her file is a signed agreement wherein she notes that the material she is working with is sensitive.

Perhaps the most intriguing thread, though somewhat impossible to follow up, is a note on her file that indicates she was expelled from the Party after a few short months of membership. This does not seem to have negatively impacted her translation career, however. In 1933, shortly before she died, Bouvier signed a new identity card to permit her to work in the headquarters of the world revolution. Quite a journey from the untroubled surroundings of Lewisham!

Note: Eugeníe’s name is sometimes spelled “Eugenia”. I have opted for the spelling she used in a 1920 letter to Sylvia Pankhurst. In Cyrillic, her name can be rendered as ЕВГЕНИЯ ГЕОРГИЕВНА БУВЬЕ

Leave a comment